Nicaragua is known as the granary of Central America: cotton, coffee and other crops grow in the small country’s fertile plains, and a lot of people – in both large and small towns – are rural producers. Students from the rural part of the country’s capital Managua, who are the children of farmers, asked the question: what can be done to increase the efficiency of plantation work?

An automated irrigation system appeared to be the best solution for Nicaragua’s student finalist group in the 2024 edition of Solve for Tomorrow – Central America and the Caribbean. The “Sensory Irrigation System” project consists of an intelligent irrigation system that uses sensors to measure soil moisture and save water, avoiding waste and improving crop efficiency.

The ninth-grade students (in Nicaragua, it is the last but one year of compulsory schooling) came up with the idea by themselves, seeing the challenges faced by their families and communities, leading with plantations, as the mediator teacher Gerald Jesús tells: “The students already had an idea of what they wanted to do. The community where they are has a lot of seed. They are the children of farmers, they are used to that. They wanted to bring about a change in their families’ lives.”

Jesus came onto the scene when the project’s concept had already been determined: the students realized that it would not be possible to come up with an entire system, but wanted to create a model, and for this, they needed a programming expert. The university professor was already teaching at the school, but he was specially invited by the students to help them with the project. It was the first time he had worked with people of such a young age.

Programming and good tests. Presentation to improve

In summary, the idea of the system was a device that could be operated from anywhere, which was connected to the common parts of a plantation, controlling irrigation depending on the soil conditions. Since the supply of electricity is intermittent in this rural area, the idea was that the system would be powered by solar panels.

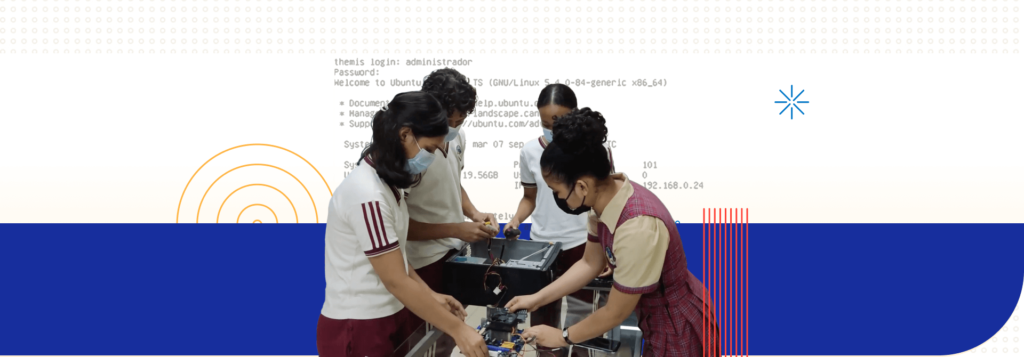

“The first step was to create a block diagram, with all the components we were going to use in the real-life model, such as humidity and temperature sensors, a water pump to regulate the amount of water, along with solar panels,” recalls the professor. Arduino, an open source hardware and software platform, was chosen because it was easier to teach it to students who had never had any contact with the subject.

The programming part took longer. “We felt that we had very little time. Here I am speaking both for myself and for the young people involved. They were under a bit of pressure because they had come up with the idea, and they were very good, but there were programming points that they did not know how to handle. When they came to me, I had a different approach with regard to how to build it and we did this in a way that fitted in with their studies and my work.”

To arrive at a prototype that would reflect the system’s effects on a plantation, the students used the following items: humidity and temperature sensors, a 5V pump, transformers, a battery, solar panels and converters.

The results of the tests of the prototype were positive, showing a battery life of between 3 and 4 days. The group felt that they could concentrate on the project’s presentation pitch, since they were shy. “We focused a lot on the demonstration part, which was very hard for the students . Dealing with a project that was new to them and learning new terms, expressing themselves in a certain way, it took a lot of effort on their part, but they succeeded.” In order to train for this, the students presented the prototype to other school classes.

A new experience for both the students and for the teacher

Although Professor Jesus had a great deal of experience with programming, it was the first time that he had ever worked alongside such young students. There were challenges in terms of teaching in this situation because, unlike the university environment, where people can leave whenever they want, it was necessary to discipline and also work on off-hour periods of classes that the young students’ parents had authorized.

Now that the prototype is a finalist and has a chance to grow, the professor is of the opinion that the students will understand how scientific knowledge can be used to improve life in their territories and communities. More than simply creating a project at school, the students can help their families and plan a future where they can grow their own crops.

Jesus points out that the Solve for Tomorrow initiative is an opportunity that shows that any student, from any region or country, can develop a unique project: “I was delighted to find out that we were participating against a lot of other countries, such as Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic. And to see the other countries’ academic level in relation to ours enables us to realize that we have the same capabilities and the same chance to compete”.