Clean up the contaminated waters of the Milotingo River, preserving agriculture and people’s health. That was the mission of the group of four students from the Joel Isidro Arce Science Club, from Colegio San Mateo de Huanchor, in the province of Huarochirí, in the department of Lima, Peru. Contaminated by heavy metals from mining operations in the region, the tributary of the San Mateo River supplies not only the local community, but the capital and other cities in the department, and its importance is fundamental for agriculture.

Mobilized by the question “what we can and what we want to transform in our community?”, the group of students went out into the field in the company of Teacher Miguel Angel Sandoval de la Cruz, to identify social issues that could be solved or mitigated through science. On these routes, the quality of water resources stood out as a point of great interest to students, who initially sought to assess the impact of mining activities on the region’s waters. “We started from hypothesis and observation, central strategies of the scientific method”, explains the teacher.

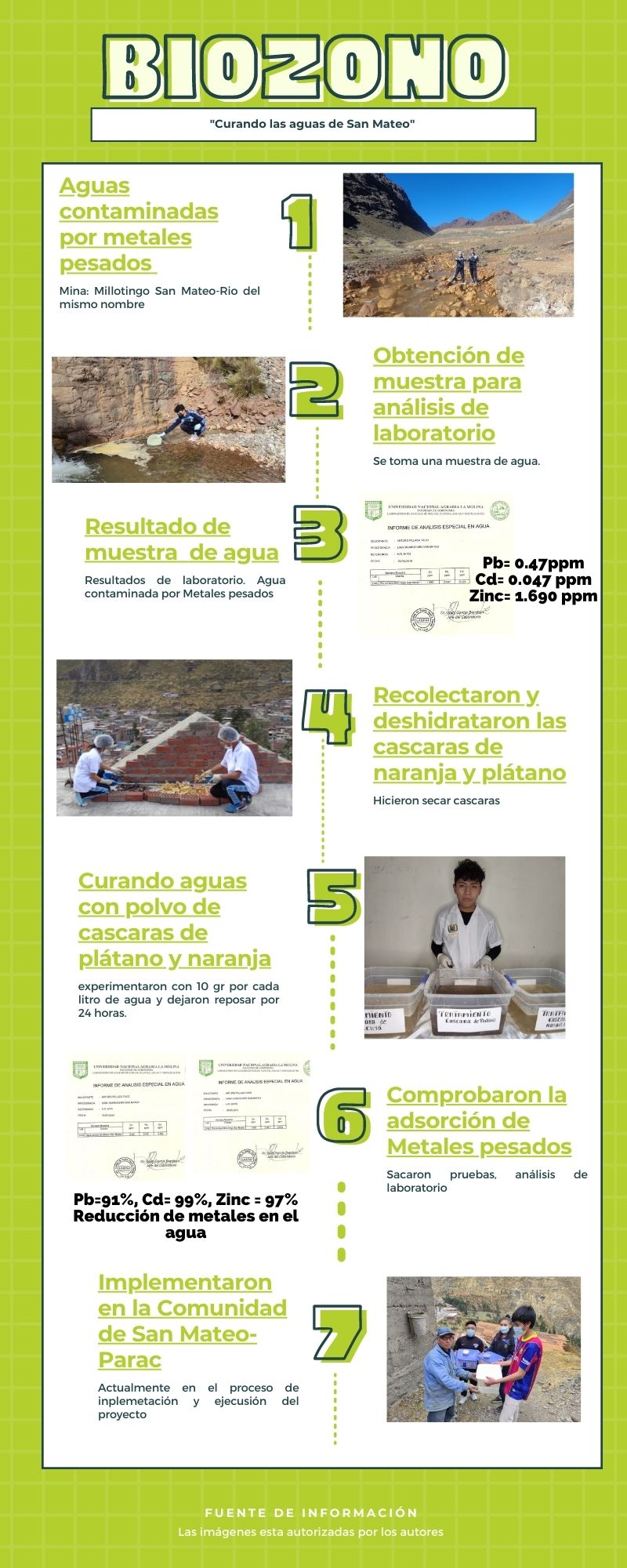

As a starting point, the students and the teacher sought the support of the Universidad Nacional Agrária La Molina to conduct a series of tests capable of measuring the presence of metals in the waters and found very concerning results. The water was indeed polluted by heavy metals. The presence of lead, for example, exceeded six times the limit allowed by Peruvian and World Health Organization parameters, and that of cadmium was up to five times more, contaminating the entire food production chain, through agriculture, pastures, and animals.

Motivated by the results, the students began to look for low-cost solutions that could be used to “cure the waters” of the river, identifying strategies that could be implemented in the community. Through reading and researching articles in scientific journals, students found the property of certain solid wastes; such as banana and orange peels, in cleaning and extracting metals from water.

The process, which is called bioremediation, manages to significantly reduce the levels of cadmium, lead, and zinc. With the support of a local mining company, the Campesina Community of San Mateo, the local public administration, and the agrarian university itself, the students started a set of tests and analyzes of water remedied by Biozono, the name given to the group’s initiative. In addition to the support of the surrounding community, teachers from different subjects were present throughout the process, from research to writing the findings.

As ideation, the students collected and dehydrated banana and orange peels, turning them into a kind of powder. Then, they performed three tests, with error control, with 5g/liter, 10g/liter, and 20g/liter, with significant results: in 24 hours of interaction, it was possible to reach 75% of absorption of lead, cadmium, and zinc, 99% and 99% respectively. Based on the experiments, the group confirmed the use of 10g of the powder extracted from the fruit peels. “To reach the results, the students needed to study the reactions that take place, mobilizing knowledge from biology, physics, chemistry, and biochemistry”, argues Miguel. Briefly, the pectin and mucilage of the orange and the cellulose and lignin of the banana, when in contact with water, form chelates that absorb the metals found.

Collaboration: school and community together to solve local challenges

After the laboratory tests, the group sought support from Comunidade Campesina, which brings together around 700 families in the region. From the collaboration of the families, they were able to develop a prototype, conducting the ideation experiments at scale and testing the bioremediation in a source of 20 liters of water. Subsequently, 10 kg of the powder were then tested in 1100 liter tanks, with results similar to the control experiments. “To involve the community, students needed to organize presentations, explain and show their experiments in public, developing a set of socio-emotional skills”, explains Miguel. For him, in addition to the scientific knowledge acquired in the process, the students developed skills to speak in public and to systematize and synthesize the information they wanted to pass on to the collectives.

Monthly, the teacher brought together the students and other partner teachers for a collective assessment. From the data collected and systematized in the different stages of the project, the teacher and the class evaluated their actions, what they could do differently, which points needed to be improved and what they had managed to achieve. Co-responsibility, listening, and dialogue among everyone were skills developed throughout the process, based on the collective exercise of being together, and doing science!