Faced with the daily challenges people with visual impairments encounter, a group of Peruvian students decided to use their creativity and knowledge to promote inclusion for people with disabilities. The team created “Pusaqkuna”, a smart stick equipped with sensors, vibration, and GPS, which enhances autonomy and safety in urban mobility. The initiative was a finalist in Solve for Tomorrow Peru 2024.

The project was developed by three 16-year-old students in the fifth and final year of secondary education. The idea emerged during a robotics class. Surrounded by daily reality — their school is located next to two hospitals — the students often saw people with visual impairments heading to medical appointments and struggling to navigate independently. “In Peru, urban design is generally not friendly to people with disabilities — whether visual, physical, auditory, or others. The students noticed this and began thinking about how robotics could provide a solution,” says Kervin Calle, art teacher and the group’s mediator.

Among the obstacles observed were poor signage, environmental noise, and a general lack of social awareness. Through a brainstorming session, they decided to create a device to help users follow a safe path. The name “Pusaqkuna” was chosen because it means “the good guide” in quechua, a language spoken in the central Andes before the Inca Empire, and still the most spoken native language in South America.

Before Solve for Tomorrow, the team had already participated in a national competition, where they performed well and were motivated to continue. “After that first experience, the main improvements were made to the prototype’s ergonomics and weight. It was too uncomfortable,” explains the teacher. At that stage, “Pusaqkuna” was a stick made of heavy metal that emitted sound alerts to signal obstacles.

I was amazed by robotics and how students begin assembling parts and programming to bring solutions to society, says Calle.

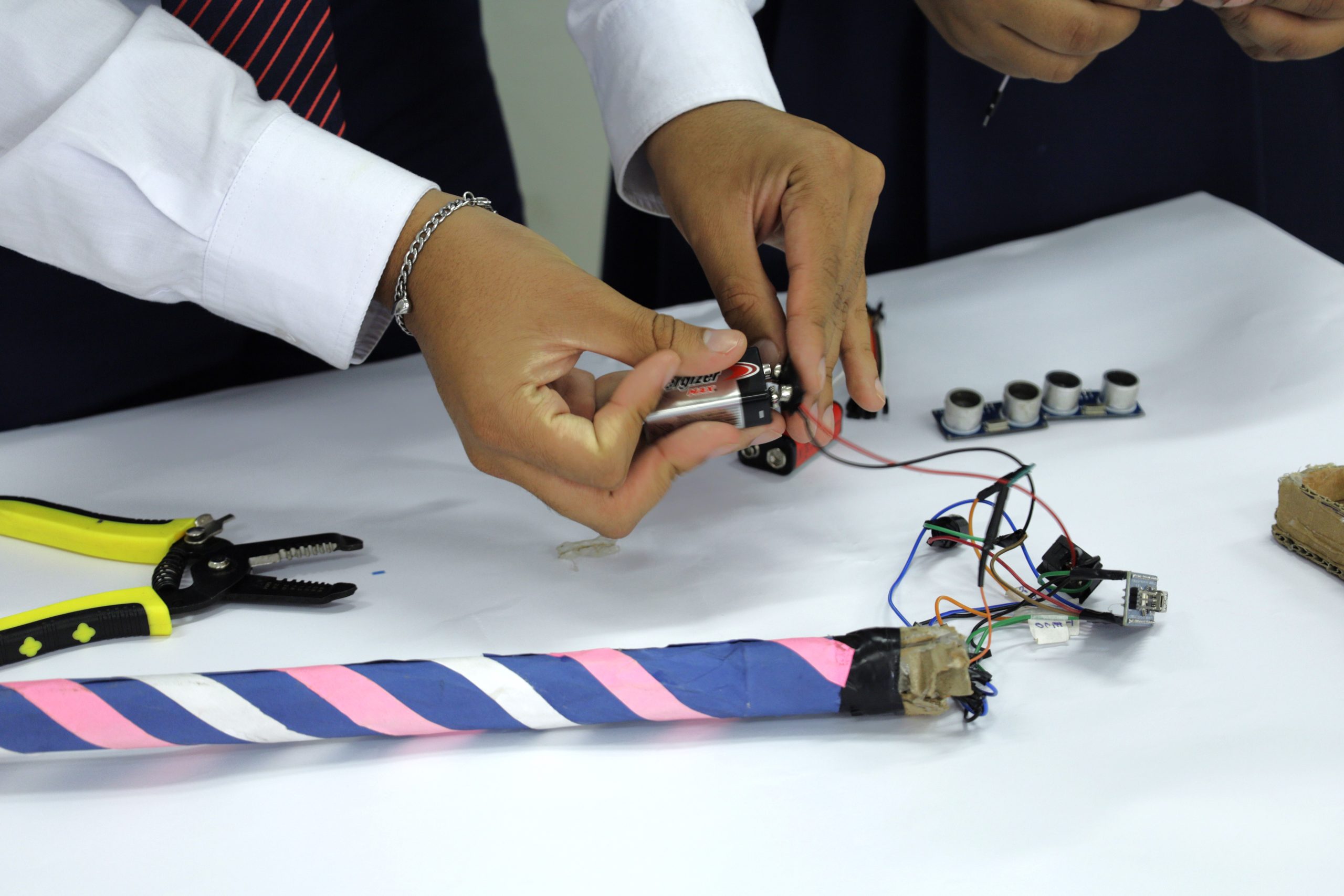

Even though Calle is not a Robotics or Mechatronics teacher, the students already had some knowledge in those areas, and other teachers supported them throughout each stage. This way, they were able to refine the final prototype. Now, when an obstacle is detected, the sensor triggers vibration in the corresponding part of the stick. For example, if there is something ahead, the front part of the stick vibrates.

The team also added LED lights to make users visible at night to other pedestrians and vehicles, increasing safety. A buzzer provides a second layer of sound alert, and their goal is to implement a GPS module that, in the future, could allow users to report dangerous obstacles — similar to navigation apps. Part of the materials was funded by the school, and the rest was covered by the students themselves. The final cost of the prototype with 3D printing was 120 soles (about 32 USD).

Working together to promote inclusion for people with disabilities

Creativity was essential for building the stick’s structure. They recycled an aluminum shower curtain rod and cut it to reduce weight. For the base, they first used cardboard and tape, and in the final version, they 3D-printed a new model that integrated an open-source Arduino Nano board, compact and ideal for portable projects.

The teacher believes that the greatest challenge wasn’t technical, but convincing the students that they had the power to solve real problems. At first, they lacked confidence, but as they completed each step, they became more motivated and excited. “They are very smart and resourceful, and they weren’t top students. This experience showed them they can make a difference — and it boosted their self-esteem,” Calle emphasizes.

Their dedication was clear: “No exaggeration, I saw the students assemble and disassemble the wiring at least 15 times. They were so committed and it was a rich and really fun learning process,” he adds.

Bringing a solution to the world

After the testing in the workshop, it was time to try it with real users — in one of the nearby hospitals and with the Union of the Blind. The main positive surprise was that this prototype didn’t cause wrist pain, unlike many devices already on the market.

From understanding how sensors work to designing the stick’s ergonomic structure, every step involved trial, error, and dedication. They conducted two feedback sessions — one at the hospital and other at the National Union of the Blind in Peru. “Some members of that organization tested the prototype and really liked it. They even asked where they could buy one. They were surprised by how light and comfortable it was,” Calle recalls.

Concerns were also raised about battery life and portability. Thanks to the Solve for Tomorrow mentorship, the team envisioned future improvements: wireless charging, mobile device integration, and making the stick foldable and even lighter.

The team is now seeking partnerships with NGOs and public institutions to scale the project, make it accessible to more people, and ensure sustainability. They are also working on new versions of the stick, integrating more features without losing sight of its core purpose: fostering autonomy and inclusion for people with disabilities.