Have you ever thought about how people with disabilities create and use music and other forms of art? Artistic manifestations depend on sensory experiences, and different ways of being and existing in the world can result in empathic solutions, rather than an obstacle. It was when they thought about this that students from a school in Chile asked themselves the question: how can we make learning music accessible for those who can’t hear?

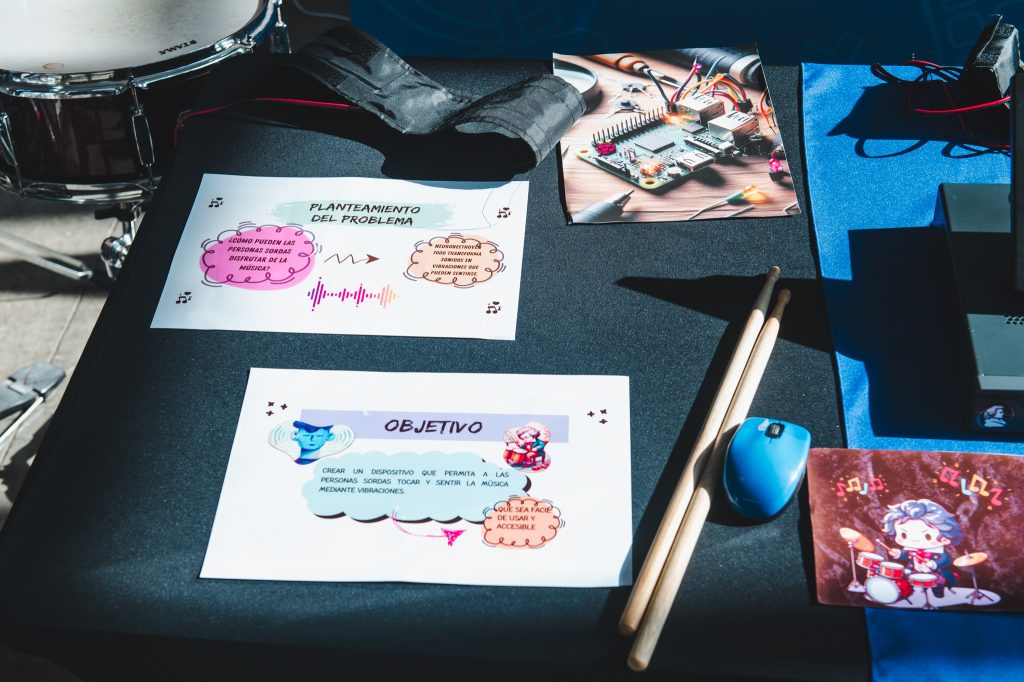

The secret lies in the vibrations, as discovered by the NeuroBeethoven group, which was one of the finalists in the Solve for Tomorrow Chile program in 2024. The students developed a device that converts sound waves into vibrations, making it possible to feel music on your skin. The project not only includes deaf people, but also became a rhythm study tool for musicians and other people interested in the musical universe.

“It was an interdisciplinary project within education”, says Rodrigo Henríquez with a great deal of pride. Rodrigo who is the initiative’s mediator and a mathematics teacher. The interdisciplinary approach can be seen not only from the fusion of technology, music and pedagogy but also from the mixed backgrounds of the group itself: the students are of different ages and at different stages of secondary education at the Manuel Bulnes Lyceum, which is located in the town of Bulnes.

Prior to the NeuroBeethoven project there was little evidence of STEM culture at the school. There was no practice of Project Based learning or use of technology as a learning tool. Henríquez and a group of teachers began to successfully implement projects of this kind, but also had to cope with a lack of materials and adequate spaces.

For the NeuroBeethoven project, the first question put to the class was: looking at your community, its problems and specific characteristics, what inspires you to undertake a project?

“A group of students came out to ask questions about problems in the community. There is a music teacher who told us that he once had a deaf student. Then the teens began to think about how they could, by using technology, take a deaf person and integrate him into music class. This was the challenge.”

Different ways of feeling music

The project got off to an ambitious start. The students wanted to create a prototype that could somehow transmit sound to deaf people. It was vital to recognize the limitations, because once they began researching the possibilities for the device, the group realized that vibrations might be the secret.

“One of the students said he had seen vibrating vests that were used at concerts so that deaf people could experience it. The idea of dealing with the vibrations to somehow integrate deaf people into music started off from this point. Within the creative process was the desire to vary the frequency, vary the rhythm”, recalls the teacher.

Even modulating the possibilities, on account of the question of time and resources, the students decided not to be overly fixated on the frequency variations, but rather on the rhythmic part. Because their aim was to enable learning and musical appreciation, they thought that percussion instruments would be excellent ones for making it possible to teach music, and for enabling a deaf person to learn to play the drums, for example.

But, as the teacher explains, it was not easy to find deaf people for research and subsequent tests: “It was super difficult to contact organizations that work with deaf people, they are super suspicious. The students were also embarrassed, I think it was a bit of a shock at first – to try and communicate with people. We tried to learn, but learning a language takes years, it’s not something that takes place from one week to the next.”

Although challenging, the conversations ended up reinforcing the bet on vibrations as being the key to everything. Students took the motors out of old cellphones and connected them to batteries and then to fabric, in order to understand how the pulses in the skin worked. To test its capability, they constructed the first prototype using motors connected to microcontrollers like Arduino, enclosed in an old printer box inside a pressure measuring cuff. Cables then connected the device to the battery.

The idea is for the person to use the cuff to perceive the rhythmic variation in learning the music while playing on the different drums and cymbals of the drum. The final prototype, after testing and improvements, is made up of: four cell phone motors, a Raspberry Pi board, connection cables, a test board, LED, a cuff for the user’s arm and an HDMI display.

Musical tests

The challenges faced by the group were by no means insignificant, given that the idea of combining music and robotics required more resources and time than was available. But the commitment of the students and the group of teachers made it possible to test the prototype, which received improvements from the very wide range of audiences that it was tested on: musicians, people who had never played an instrument as well as people who were deaf.

“The first thing we noticed was that people who play drums had a bit of trouble finding the rhythm at first, but once they met, they were on their own. The interesting thing was the people who didn’t play drums. We realized that there is a group that made it very easy and another group that took a lot to learn. So there’s a theme, apparently, that there are people who have the facility to pick up the pace and keep up with it. There are people who would sit at the drums and in the space of 5 minutes they were playing the drums, even though they’d never done that before.”

The results with deaf people also revealed that even among this group there can be different interpretations of vibrations. One person may have greater difficulty identifying rhythmic variations while another found it easier. But overall it was easy, which was important for the project. Deaf people may be more sensitive to vibrations and able to play instruments.

After being selected as one of the finalists of the program Solve for Tomorrow, the idea is to take advantage that there is time and students who are still on the learning path to improve the prototype: to obscure the cables using Bluetooth intelligence, to add frequencies and other musical nuances to the prototype, and to understand how to connect them to other instruments.

There were marked changes in the students’ lives, according to the professor: “We have made students hungry, expanding their vision for the future, with some of them wanting to study technology at Harvard. All the students who have taken part in this initiative have ended up at university, studying law, medicine and science.”

Last but not least, in Henríquez’s opinion, the project’s real power is the possibility of merging disciplines: “It’s that somehow we have to try to work in an interdisciplinary way within education. We still have one hour of math, then history and then music. But it may be much more enriching if the history, math and music teachers find a way to have classes that combine all of these disciplines.”