La Junta, a rural area of San Juan del Cesar, Colombia, is far from major commercial centers. So, even when local farmers have good harvests, they often can’t reap the expected benefits, as many are unable to afford the fuel costs needed to travel and sell their products. Observing this reality, three young people realized the solution was right before their eyes: in the cactus plants.

This desert plant has a high content of compounds and is rich in sugar, which makes it suitable for conversion into alcohol. Thus, it can be transformed into biofuel to power vehicles. The creation, named “Biocombustible Juntero,” received an honorable mention at Solve for Tomorrow Colombia in 2024.

The students carried out a process similar to that of ethanol, a common fuel in Latin America as an alternative to gasoline. The cactus was chosen because it is very abundant in La Junta and could be collected for free. “In fact, it’s a plant considered invasive since there’s no control over its spread. Now, we’re giving it a purpose with a great benefit,” explains the mediator teacher, Stefany Rodriguez, who is a Mining Engineer and Math teacher.

Two 11th-grade students and one from 10th grade participated—the final years of compulsory education. Each was responsible for a task: José José Oñate handled prototyping, Estefany Montero led the research and problem structuring, while Amalfi Sara focused on validation, analysis with experts, and interviews with transporters.

The idea was to offer an affordable and sustainable solution, especially for the community’s transporters and farmers. “We saw the difficulty within our own families. This is a community that is constantly limited in its development due to high transportation costs and difficulty accessing fuel,” says Rodriguez.

According to her, some student’s relatives would lose part of their agricultural production because they couldn’t afford transportation to distant markets. “We thought: how can we change this? Not only to relieve the burden on the community but also to show that even from a rural area like ours, we can make a difference,” the teacher recalls.

Learning begins with the teacher

The educator is also from San Juan del Cesar, but from the urban area. Working in the rural area of La Junta has been a challenge for her, especially due to lack of internet connectivity. “We tried to take advantage of that limitation and explore other strategies with our students,” she shares. One of the ways was to implement Project-Based Learning. So, when she came across a Solve for Tomorrow announcement, she decided to apply with her students. She guided around 30 projects, resulting in three finalist projects.

Previously, the teacher had no experience with Design Thinking but learned throughout the program through training and mentorships. One of the practices she adopted was actively listening to the target audience—from Empathy to Testing. “We went out into the field, conducted interviews, and with every progress, we shared it with the transporters,” she recalls. Around ten farmers were interviewed, and most said they were willing to use the biofuel.

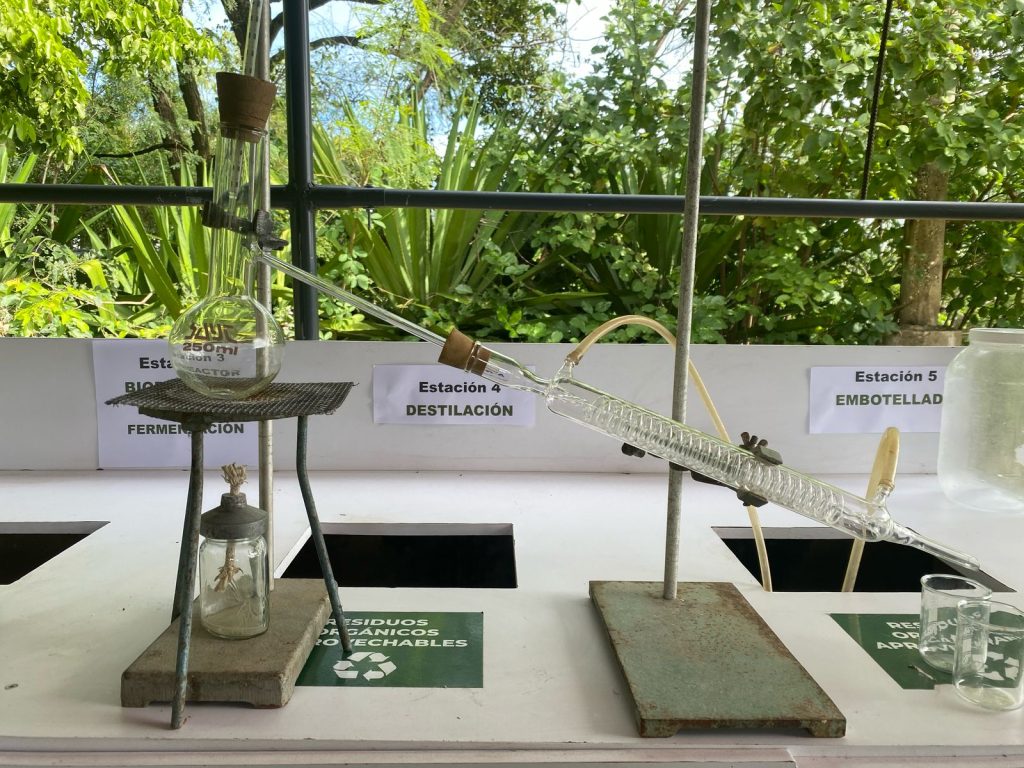

With the research in hand, the team designed a mobile biorefinery lab capable of processing the biomass of desert plants into a renewable energy source. After processing the cactus biomass, the group fermented it using local microorganisms adapted to the desert conditions of the rural area. This biofuel was then distilled.

The future of our rural communities lies in seeking local, sustainable, and affordable alternatives, she believes.

Producing renewable energy

The team also used a bioreactor, a device that facilitates microorganism growth, which in this case were responsible for fermentation. Besides the teacher’s blender, all materials were reused from what they already had at home, like plastic and glass containers. However, to measure results, they had to obtain a pH meter, an electroanalytical instrument used to measure the pH of a solution.

Now, the team plans to continue scaling the project by conducting tests on a motorcycle, the community’s primary means of transportation. “I believe it was a very meaningful learning experience for the students, showing how to contribute to sustainable development,” says the teacher. Rodriguez shares that the group reflected on the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) when designing the project. They initially focused on affordable and clean energy and later realized they also promote responsible production and consumption by repurposing organic waste. This reduces waste generation and fosters a circular economy model, which involves sharing, renting, reusing, repairing, refurbishing, and recycling materials and products as much as possible to create added value. “With creativity, we bring solutions to many issues,” she explains.

She also notes that the experience encouraged students to express themselves more, as they were shy at first. “To teachers wanting to start a similar project, I would say it’s important to fully experience every stage—empathy, ideation, prototyping—and to remember that every idea counts,” she advises.